Getting diagnosed with breast cancer brings a lot of physical and emotional challenges. Beyond the physical side effects of breast cancer treatments, there are emotional hurdles that come with a diagnosis, treatment, and recovery. Fortunately, there is evidence showing that exercise can help to ease both the physical and emotional burdens of breast cancer. In this blog, we will explore the different types of exercise that can help, the physical and mental benefits exercise and see what an Exercise and Cancer Specialist has to say.

What is exercise?

Exercise, or physical activity, is defined as any movement that uses your muscles and burns more energy than resting1. This can be anything from walking, running, cycling, dancing, or even doing household chores. Staying active is important, especially for people with a cancer diagnosis.

What types of exercise are there?

There are different types of exercise, each offering unique benefits:

- Strength training: Strength or resistance training is when the exercise is designed to increase your muscle mass, by adding strain or weight to your muscles2. Exercise examples include using weight machines, handheld weights, resistance bands, or even your own body weight (push ups).

- Aerobic training: Cardiovascular or aerobic training (also known as cardio) involves using large muscle groups to raise your heart and breathing rates2. You should be able to maintain the exercise you are doing for a prolonged period of time as it is usually low intensity e.g. include walking, running, swimming, cycling and dancing.

- Balance and stretch exercises: Activities like yoga and Pilates. These can often combine both aerobic and resistance training and. can be hugely beneficial for improving flexibility, balance and overall wellbeing3.

It is important to remember that you should consult your doctor before starting a new exercise routine and listen to your body to avoid pushing yourself too far and causing any harm.

What are the benefits of exercise for breast cancer patients?

Strength and mobility: Engaging in various forms of physical activity can build strength, stamina, and overall fitness. This has been shown to improve energy and how patients handle tasks from day-to-day life4,5. It also puts patients in a better position to cope with the demands of treatment6.

Managing side effects: Exercise can alleviate fatigue and help manage other side effects like insomnia, shortness of breath (dyspnoea), nausea, and lymphoedema1,7,8, which are common concerns during and after treatment.

Do you know that you can track your side effects with OWise? With more than 30 side effects and symptoms to choose from, you can track any changes and share these with your care team and loved ones via a secure hyperlink. Having a better communication with your care team can make sure you receive the best care possible.

Bone health: Certain breast cancer treatments, like aromatase inhibitors can weaken bones and increase the risk of osteoporosis, fractures and breaks9. Weight bearing exercises, resistance training combined with light aerobic exercise, help to maintain and improve bone density, reducing the risk of bone damage8,10.

Weight management: Weight gain is a common side effect of certain breast cancer treatments, which can affect quality of life, mobility, and body image11. Regular exercise is a proven method for burning fat and building muscle, helping patients to reach and maintain a healthy weight.

Pain management: Exercise releases endorphins, making it great for mental and physical health. It can alleviate chronic pain caused by cancer and its treatments improving the quality of life for those experiencing discomfort1,8,12.

Immune system benefits: There is evidence that exercise boosts the immune system13. Staying active during immunotherapy and other treatments can help the body fight infections and strengthen the immune response against cancer.

Can exercise help mental health?

Exercise not only changes your body physically, but there are years of research showing regular exercise can hugely benefit your mental and emotional health14,15.16. Particularly with breast cancer, there can be a range of emotional side effects that accompany a diagnosis, treatment, surgery, or recovery into years of survival16,17.

Stress and anxiety relief: exercise has been a proven stress and anxiety reliever, as it promotes the release of hormones associated with mood elevation such as dopamine and serotonin18. Lack of exercise also contributes to increased stress levels, so gentle physical activity can help with symptoms of stress and anxiety around breast cancer.

Body image: breast cancer and its treatments can cause body changes that can contribute to poor body image19. Doing exercise not only gives you added physical strength, but this can translate into feeling strong and capable mentally, boosting your self-esteem and self-worth. As weight loss also accompanies exercise, reaching a healthy weight can positively impact how you see yourself, making you feel more powerful.

Empowerment: breast cancer can sometimes make you feel like you have lost control over your health and sense of self, but taking back control by exercising can empower you towards recovery and provide a sense of strength back in yourself.

Social support: group exercise classes and support groups can provide you with a sense of community, making you feel less isolated during breast cancer. Many people find that speaking with others who are dealing with a similar situation, and working through the struggle together (i.e., exercising together) can be more beneficial than trying to tackle it alone24.

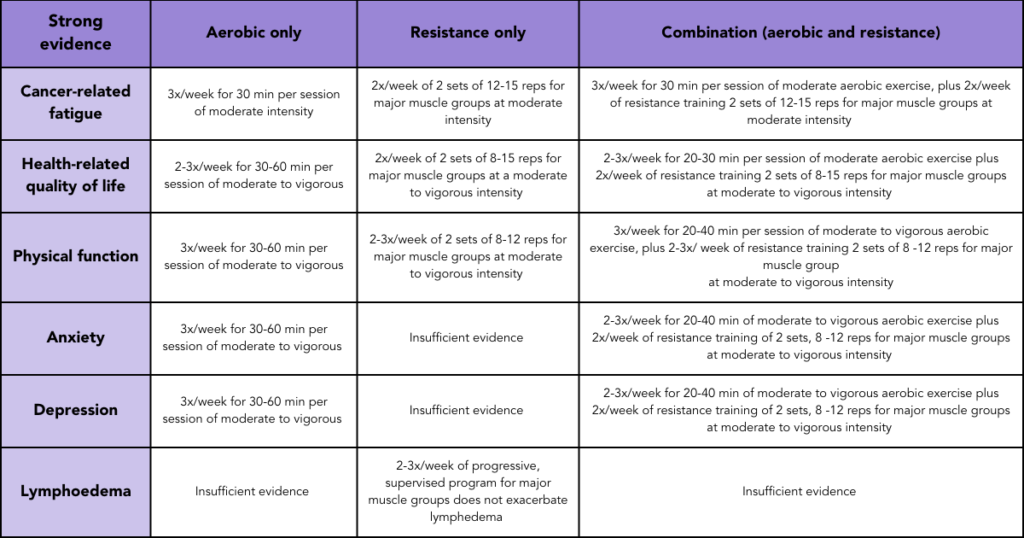

Table 1. Types of aerobic and resistance exercise that there is strong evidence to help relieve certain cancer- or treatment-related side effects. Adapted from the American College of Sports Medicine guidelines31.

Is exercise important for breast cancer survivors?

Research strongly supports the benefits of exercise for breast cancer survivors1,4,9,21,22,23. Staying physically active post-cancer significantly reduces the risk of death and recurrence. A 2019 review highlighted that women who were more physically active after breast cancer had a 42% lower risk of death from any cause and a 40% lower risk of death from the breast cancer coming back than those who were sedentary1,24.

What exercises can I do?

Before starting any exercise routine, you should always consult your doctors to ensure it is safe for you, especially considering factor such as recent surgery, side effects and other pre-existing health conditions.

The general guidelines for adults to exercise healthily include 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week25. Similar effects can also be seen by doing 75 minutes of intensive exercise per week, but this is not as commonly recommended for cancer patients.

What does a breast cancer and exercise specialist have to say?

Sarah who after her own Cancer Diagnosis, retrained as a Cancer & Exercise Specialist to help support others like her, keen to exercise after a Cancer diagnosis but unsure where to start. She has created a programme, Get Me Back, to get those who have had a cancer diagnosis back to training, with confidence. You can get in touch with Sarah at www.getmeback.uk or on Instagram @getmebackuk

Why is strength training so beneficial to those with a breast cancer diagnosis?

Strength or resistance training is a type of exercise that helps build muscle mass using anything from bodyweight and resistance bands to dumbbells and more. There are lots of things around the house you can use too! Strength training helps those in active treatment to maintain muscle mass, counteracting the effects some treatments have on muscle wastage26. Research is also beginning to show that those with a greater muscle mass can improve treatment outcomes27.

Furthermore, strength training can improve bone density, reducing the risk of developing osteoporosis28.Progressively building up the resistance put through joints means you can remain active and mobile for longer, thriving into later life, doing all the many things you want to do for longer. Instead of training for a bikini body, I now train to be a fit and healthy older woman!

What advice do you give to someone newly diagnosed who wants to improve their fitness levels?

It can feel like a completely impossible time to exercise when you’ve been diagnosed with cancer. And I totally understand that many feel like this is the last thing you want to do. From my own personal experience, exercise felt like something I was in control of, particularly at the start when my emotions were all over the place. I wanted to prove I could still do it and that I was in charge. One major mind shift I had after my own diagnosis was how I saw exercise. Exercise was no longer something I sometimes reluctantly did to help with weight loss and aesthetic reasons, it became a necessity for my health and recovery.

If you’ve just been diagnosed, I would suggest trying to see exercise as a tool or medicine that can help you, not something you should feel forced to do. Start by thinking about the type of movement you enjoy – dancing, walking, gardening – and start there. Movement is useful at all stages of treatment, but like all medicines, its dose is personal to you.

Before treatment starts, if you feel well enough, try and get as fit as possible – walk, run, cycle – building up your time or pace each day. The fitter you are before you start, your quality of life is more likely to be improved before and after treatment29.

Can exercise help with treatment side effects?

During treatment, research has shown that by combining aerobic exercise (like walking) and a couple of short strength-based sessions (even using your bodyweight) every week, can significantly reduce treatment side effects such as cancer-related fatigue, nausea, anxiety, health-related quality of life and your everyday physical functioning30 .

It may feel extremely counterintuitive, but from personal experience, I found that on the days I got out of bed and walked around the block in the morning, I had so much more energy for the rest of the day. The dose of exercise needs to be right for you – the advice is exercise for energy, not exhaustion. So, start low and work up, keeping a note of how it makes you feel. Keep up regular stretching too as this will help with any ongoing stiffness.

What steps can someone take after treatment to help make them feel stronger?

My advice would be to start with a simple daily walk, building on the time you are walking every few days. As you start to feel stronger, introduce some different types of movement like yoga and stretching. Then when you’re ready, begin to add in strength training. You can seek advice from a cancer and exercise specialist to support you. They are trained to understand the best approaches to exercising after a cancer diagnosis. My company, Get Me Back, offer a breast cancer fitness recovery programme which takes women through weekly exercise videos to help them progressively get stronger whilst regaining upper body mobility, core strength and cardiovascular fitness.

With breast cancer bones can be impacted by early menopause. What is the best thing women can do to help their bone health?

Definitely strength training. Progressively putting more load (weight/resistance) through your bones will help increase your bone density. Many women find approaching this type of exercise quite daunting and can be put off by gym equipment or group classes. What I try to teach women is that strength training is based on functional movements we use every day – like getting in and out of a chair, bending to pick up something from the floor, pushing and pulling doors.

Why is strength training so beneficial to those with a breast cancer diagnosis? Any tips to help motivate someone to start incorporating exercise into their lives?

I think we should all have a huge amount of respect for what our bodies have been through because of cancer. We need to treat it with care and look after it. Exercise should be a non-negotiable appointment we have with ourselves, just like we would turn up to any medical appointment. If you’re lacking in motivation, make sure you go back to your reason ‘why’ – why are you exercising? I write this on a post-it note and stick it on my fridge door to remind myself. A few other tips to help:

- On a workout day, get dressed in your gym gear. Don’t change until you’ve done your exercise

- Progress slowly, don’t wipe yourself out on day 1 – remember to exercise for energy not exhaustion

- When you feel great after a workout, write down that feeling and stick it somewhere to remind yourself

- Take some friends with you for support or build your exercise into a social meet-up

- Find a trainer who you like and knows how to support you after cancer

And that’s exercise and breast cancer summed up

A breast cancer diagnosis comes with many physical and emotional challenges. Fortunately, research supports the benefits of exercise in alleviating these burdens. We hope this blog has made you more aware of the benefits of exercising, from managing side effects like fatigue and insomnia to enhancing bone health and supporting mental resilience. If you would like to get in contact with Sarah for specialist advice you can get in touch with her at www.getmeback.uk or on Instagram @getmebackuk.

At OWise, we want to make sure you are kept informed so make sure to follow our Instagram and Facebook for any updates. Any questions? Get in touch!

References

- National Cancer Institute. Physical Activity and Cancer. National Cancer Institute. 2020 Feb 10. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/obesity/physical-activity-fact-sheet

- Mya Care. STRENGTH TRAINING VS AEROBIC EXERCISE: WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE? | Mya Care. myacare.com. 2022. https://myacare.com/blog/strength-training-vs-aerobic-exercise-whats-the-difference#:~:text=Aerobic%20exercises%20are%20mainly%20low

- Lim E-J, Hyun E-J. The Impacts of Pilates and Yoga on Health-Promoting Behaviors and Subjective Health Status. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(7):3802. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073802

- McNeely ML. Effects of exercise on breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2006;175(1):34–41. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1482759/. doi:https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.051073

- Hacker E. Exercise and Quality of Life: Strengthening the Connections. Clinical journal of oncology nursing. 2009;13(1):31–39. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2885352/. doi:https://doi.org/10.1188/09.CJON.31-39

- Ficarra S, Thomas E, Bianco A, Gentile A, Thaller P, Grassadonio F, Papakonstantinou S, Schulz T, Olson N, Martin A, et al. Impact of exercise interventions on physical fitness in breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review. Breast Cancer. 2022;29(3):402–418. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-022-01347-z

- ROGERS LQ, COURNEYA KS, SHAH P, DUNNINGTON G, HOPKINS-PRICE P. Exercise stage of change, barriers, expectations, values and preferences among breast cancer patients during treatment: a pilot study. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2007;16(1):55–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00705.x

- Mustian KM, Sprod LK, Palesh OG, Peppone LJ, Janelsins MC, Mohile SG, Carroll J. Exercise for the Management of Side Effects and Quality of Life Among Cancer Survivors. Current Sports Medicine Reports. 2009;8(6):325–330. doi:https://doi.org/10.1249/jsr.0b013e3181c22324

- Royal Osteoporosis Society. Royal Osteoporosis Society | Breast cancer treatments. theros.org.uk. 2016. https://theros.org.uk/information-and-support/osteoporosis/causes/breast-cancer-treatments/

- Almstedt HC, Grote S, Korte JR, Perez Beaudion S, Shoepe TC, Strand S, Tarleton HP. Combined aerobic and resistance training improves bone health of female cancer survivors. Bone Reports. 2016;5:274–279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bonr.2016.09.003

- Macmillan. Managing weight gain after cancer treatment. 5th ed. Macmillan Cancer Support; 2020. https://www.macmillan.org.uk/dfsmedia/1a6f23537f7f4519bb0cf14c45b2a629/2981-source/mac12167-managing-weight-gain.pdf

- Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017;4(4). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5461882/. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd011279.pub3

- Gustafson MP, Wheatley-Guy CM, Rosenthal AC, Gastineau DA, Katsanis E, Johnson BD, Simpson RJ. Exercise and the immune system: taking steps to improve responses to cancer immunotherapy. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. 2021;9(7):e001872. https://jitc.bmj.com/content/9/7/e001872. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2020-001872

- Imboden C, Claussen MC, Seifritz E, Gerber M. [The Importance of Physical Activity for Mental Health]. Praxis. 2022;110(4):186–191. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35291871/. doi:https://doi.org/10.1024/1661-8157/a003831

- Taylor C, Sallis J, Needle R. The relation of physical activity and exercise to mental health. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):195–202.

- Zanghì M, Petrigna L, Maugeri G, D’Agata V, Musumeci G. The Practice of Physical Activity on Psychological, Mental, Physical, and Social Wellbeing for Breast-Cancer Survivors: An Umbrella Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(16):10391. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610391

- Spiegel D. Psychosocial aspects of breast cancer treatment. Seminars in Oncology. 1997:S1-36S1-47.

- Schultchen D, Reichenberger J, Mittl T, Weh TRM, Smyth JM, Blechert J, Pollatos O. Bidirectional relationship of stress and affect with physical activity and healthy eating. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2019;24(2):315–333. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6767465/. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12355

- Helms RL, O’Hea EL, Corso M. Body image issues in women with breast cancer. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2008;13(3):313–325. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500701405509

- Mortazavi S, Shati M, Ardebili H, Modammad K, Beni R, Keshteli A. Comparing the Effects of Group and Home-based Physical Activity on Mental Health in the Elderly. International Journal of Preventive Medicine . 2013;4(11):1282–1289.

- Martínez-Vizcaíno V, Cavero-Redondo I, Reina-Gutiérrez S, Gracia-Marco L, Gil-Cosano JJ, Bizzozero-Peroni B, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Ubago-Guisado E. Comparative effects of different types of exercise on health-related quality of life during and after active cancer treatment: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2023;12(6). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2023.01.002

- CAMPBELL KL, WINTERS-STONE KM, WISKEMANN J, MAY AM, SCHWARTZ AL, COURNEYA KS, ZUCKER DS, MATTHEWS CE, LIGIBEL JA, GERBER LH, et al. Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2019;51(11):2375–2390. doi:https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000002116

- Schmitz KH, Campbell AM, Stuiver MM, Pinto BM, Schwartz AL, Morris GS, Ligibel JA, Cheville A, Galvão DA, Alfano CM, et al. Exercise is medicine in oncology: Engaging clinicians to help patients move through cancer. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2019;69(6):468–484. doi:https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21579

- Spei M-E, Samoli E, Bravi F, La Vecchia C, Bamia C, Benetou V. Physical activity in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis on overall and breast cancer survival. The Breast. 2019;44:144–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2019.02.001

- Department of Health and Social Care. UK Chief Medical Officers’ Physical Activity Guidelines. Crown; 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832868/uk-chief-medical-officers-physical-activity-guidelines.pdf

- Thorsen L, Nilsen TS, Raastad T, Courneya KS, Skovlund E, Fosså SD. A randomized controlled trial on the effectiveness of strength training on clinical and muscle cellular outcomes in patients with prostate cancer during androgen deprivation therapy: rationale and design. BMC Cancer. 2012 [accessed 2020 Apr 10];12(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-123

- Takayuki Shiroyama, Izumi Nagatomo, Koyama S, Hirata H, Nishida S, Miyake K, Fukushima K, Shirai Y, Mitsui Y, Takata S, et al. Impact of sarcopenia in patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer treated with PD-1 inhibitors: A preliminary retrospective study. Scientific Reports. 2019 [accessed 2023 Jul 27];9(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39120-6

- Benedetti MG, Furlini G, Zati A, Letizia Mauro G. The Effectiveness of Physical Exercise on Bone Density in Osteoporotic Patients. BioMed Research International. 2018;2018(4840531):1–10. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2018/4840531/. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4840531

- Cancer Research UK. How do I physically prepare for cancer treatment? | Prehabilitation | Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org. 2024. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/treatment/prehabilitation/be-physically-active

- Cataldi S, Amato A, Messina G, Iovane A, Greco G, Attilio Guarini, Fischetti F. EFFECTS OF COMBINED EXERCISE ON PSYCHOLOGICAL AND PHYSIOLOGICAL VARIABLES IN CANCER PATIENTS: A PILOT STUDY. Acta Medica Mediterranea. 2020;36:1105. https://iris.unipa.it/retrieve/handle/10447/509526/1210615/Effects_of_combined.pdf. doi:https://doi.org/10.19193/0393-6384_2020_2_174

- ACSM. What can exercise do? https://www.acsm.org/docs/default-source/files-for-resource-library/cancer-infographic-sept-2022.pdf