What is BRCA?

BRCA stands for breast cancer susceptibility gene. There are two of these genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2, the former first discovered by Mary-Claire King in the 1980’s. Their function is to help repair damaged DNA, preventing the development of tumours. There are certain variants of these genes that can result in a loss of their function whereby the mechanism to repair DNA is compromised. This may mean that any damage to the DNA is not adequately repaired and as a result, cells are more likely to develop additional genetic alterations that can lead to cancer.

Inheritance of BRCA variant genes

BRCA genes are hereditary, meaning you receive a copy of each gene from both parents. If someone has inherited a faulty version of the BRCA gene from one or both parents, they have an increased risk of developing breast cancer. Assembling a family history of cancer is crucial in assessing a person’s potential risk. Both first-degree (parents, siblings, children) and second-degree (aunts, uncles, cousins) relatives’ history are required for a comprehensive evaluation. The current guidelines within the NHS suggest a genetic test if cancer runs in a family. This type of testing will indicate whether the person has inherited one or more cancer risk genes.

BRCA genes are hereditary, meaning you receive a copy of each gene from both parents. If someone has inherited a faulty version of the BRCA gene from one or both parents, they have an increased risk of developing breast cancer. Assembling a family history of cancer is crucial in assessing a person’s potential risk. Both first-degree (parents, siblings, children) and second-degree (aunts, uncles, cousins) relatives’ history are required for a comprehensive evaluation. The current guidelines within the NHS suggest a genetic test if cancer runs in a family. This type of testing will indicate whether the person has inherited one or more cancer risk genes.

The choice of taking a genetic test is solely up to the individual. Knowledge of risk can allow for early management, including regular breast examinations, alternative screening types such as ultrasound and MRI and adopting risk reduction strategies.

Impact of prior knowledge of faulty BRCA genes

Not only does detection prior to diagnosis increase the chance of earlier detection, an Israeli study1 found that women carrying faulty BRCA1/2 genes who develop breast cancer appear to fare better if their genetic risk was detected prior to their cancer diagnosis, even if they do not undergo preventative procedures such as risk-reduction surgery.

Although the group of women with prior knowledge and those without were roughly the same age when diagnosed with cancer, those with prior knowledge of their BRCA gene status were diagnosed with less invasive forms of breast cancer compared to those unaware. They also had a higher overall survival advantage, despite similar breast cancer grades, hormone receptors status and subtypes in both groups. These effects are likely due to the increased awareness of breast cancer and therefore the ability to catch it at an earlier stage.

BRCA variant genes in the risk of cancer

In the general population, 1 in 8 women develop breast cancer during their lifetime. With a faulty BRCA gene, this risk increases. For someone with a BRCA mutation there is a 70% chance (or 70 out of 100 people) to develop breast cancer by the age of 802. Those associated tend to develop in younger women and be present in both breasts. Of all breast cancer cases, 5-10% are associated with faulty variants of the BRCA genes. However, the profiles of the development of cancer caused by BRCA1 and BRCA2 differ as they also may cause ovarian cancer. Whilst commonly only 1 in 100 women will get ovarian cancer during their lifetime, a BRCA1 variant gene increases the incidence to 44 women. Faulty BRCA2 genes have less association with ovarian cancer, with 17 out of 100 women likely to develop it. Defective BRCA2 genes don’t just affect women. Men with a faulty BRCA2 gene are 80 times more likely to develop breast cancer, as well as 7 times more likely to develop prostate cancer.

Targeted treatments for BRCA

PARP inhibitors are an emerging treatment for BRCA positive individuals. Normally the PARP proteins help repair damaged DNA inside cells. By stopping these proteins working, on top of the decreased DNA repair from the faulty BRCA gene, the damage to the DNA often leads to the death of tumour cells.

Olaparib (Lynparza®)

Olaparib (Lynparza®) was recently approved by NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) to treat high risk early HER2-negative (HER2-) breast cancer in patients with a BRCA mutation (BRCA+), after having surgery and chemotherapy treatment7. High risk means there must be at least 4 positive lymph nodes, 1-2 lymph nodes with grade 3 disease, tumour size of at least 5cm, or there are still signs of cancer after receiving treatment before surgery. Olaparib can be prescribed alone or with hormone therapy to treat hormone receptor-positive (HR+)/HER2- BRCA mutated breast cancer.

The OlympiA trial compared olaparib vs placebo in 1836 patients with early HER2-/BRCA+ breast cancer. This is the first trial to investigate a treatment which targets early stage BRCA-mutated breast cancer specifically4. The results demonstrated that when comparing olaparib to placebo, olaparib kept 83% of patients free of invasive disease for 4 years versus 75% of those on placebo8. It was also found that the risk of death was reduced by 32% in patients taking olaparib compared to patients on placebo.

Olaparib is also approved in the US to treat secondary (metastatic, advanced) HER2-/BRCA+ breast cancer patients after chemotherapy treatment9.

Talazoparib (Talzenna®)

Talazoparib (Talzenna®) is a PARP inhibitor that can be used to treat HER2- breast cancer patients that are BRCA+ in the US. Positive results from the EMBRACA trial lead to approval in the US10. The trial compared talazoparib vs the physicians choice of chemotherapy in 431 patients with locally advanced or metastatic HER2-/BRCA+ breast cancer. It was found most patients on talazoparib went on 8.6 months without the cancer growing or spreading, compared to 5.6 months on chemotherapy treatment11.

Talazoparib is currently being reviewed by NICE in the UK.

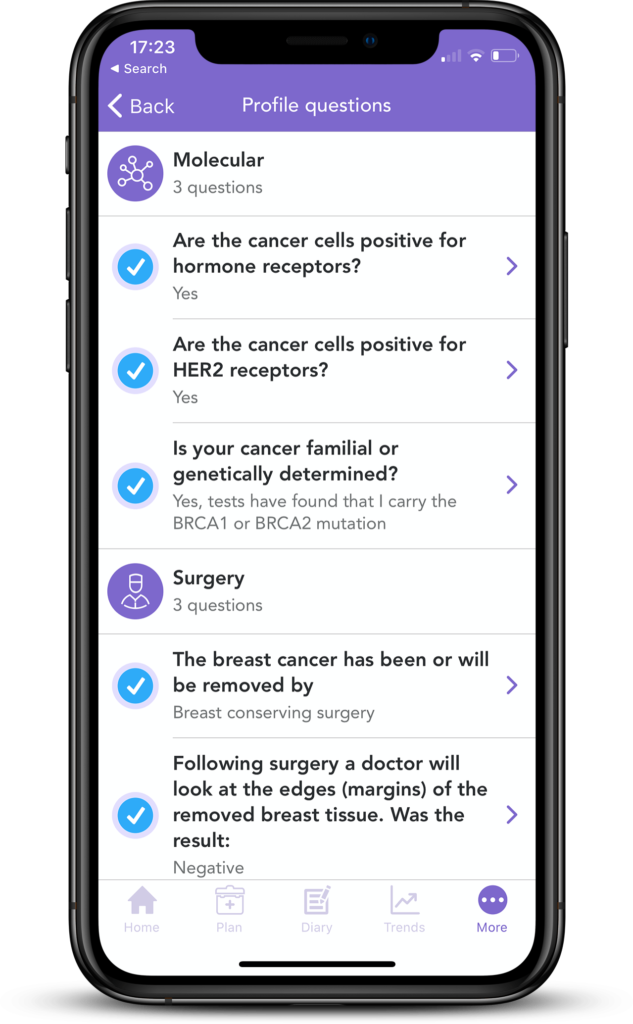

If you have been tested positive for BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene variants, you can add this into your OWise profile. Your personalised treatment report will then give you a thorough description of how this may impact screening, treatment and suggestions to manage the risk to developing cancer.

Did you find this interesting? Let us know below!

Useful links/Read more

National Breast Cancer – https://www.nationalbreastcancer.org/what-is-brca

Cancer.gov – https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/genetics/brca-fact-sheet

NHS – https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/predictive-genetic-tests-cancer/

Breast Cancer Now – https://breastcancernow.org/information-support/facing-breast-cancer/going-through-breast-cancer-treatment/parp-inhibitors-in-breast-cancer-treatment

References

- Hadar T, Mor P, Amit G, Lieberman S, Gekhtman D, Rabinovitch R et al. (2020) Presymptomatic Awareness of Germline Pathogenic BRCA Variants and Associated Outcomes in Women With Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncology.

- Barnes D, Phillips K, Mooij T, Roos-Blom M et al. (2017). Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA. 317(23):2402-2416

- “Olaparib as Adjuvant Treatment in Patients With Germline BRCA Mutated High Risk HER2 Negative Primary Breast Cancer – Full Text View.” Olaparib as Adjuvant Treatment in Patients With Germline BRCA Mutated High Risk HER2 Negative Primary Breast Cancer – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov, clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02032823.

- “Trial Shows Benefits of Targeted Drug against Early-Stage Breast Canc.” The Institute of Cancer Research, www.icr.ac.uk/news-archive/trial-shows-benefits-of-targeted-drug-against-early-stage-breast-cancer-with-inherited-brca-mutation.

- Tutt, Andrew N.j., et al. “Adjuvant Olaparib for Patients with BRCA1- or BRCA2-Mutated Breast Cancer.” New England Journal of Medicine, 2021, doi:10.1056/nejmoa2105215.

- https://www.merck.com/news/lynparza-olaparib-reduced-risk-of-death-by-32-in-patients-with-germline-brca-mutated-her2-negative-high-risk-early-breast-cancer-in-phase-3-olympia-trial/

- Olaparib for adjuvant treatment of BRCA mutation-positive HER2-negative high-risk early breast cancer after chemotherapy. (2023) NICE. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta886

- Geyer et al. (2022) Overall survival in the OlympiA phase III trial of adjuvant olaparib in patients with germline pathogenic variants in BRCA1/2 and high-risk, early breast cancer. Annals of Oncology.

- FDA approves olaparib for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic breast cancer. (2018) FDA. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-olaparib-germline-brca-mutated-metastatic-breast-cancer

- FDA approves talazoparib for gBRCAm HER2-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. (2018) FDA. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-approves-talazoparib-gbrcam-her2-negative-locally-advanced-or-metastatic-breast-cancer

- Litton et al. (2018) Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer and a Germline BRCA Mutation. New England Journal of Medicine, 379:753-763.